Edgar Leeteg: The Father of Modern Velvet Painting

Edgar Leeteg was in his 20s when he first visited Tahiti. While working as a billboard painter for an advertising agency in Sacramento, he had decided to take a six-week vacation to Tahiti 1930. He chose the Tahitian vacation simply because it was the only one he could afford out of the travel brochures he was presented with.

His initial impressions of Tahiti were mixed. The Tahitian government demanded almost half of his pocket money as a “landing tax” on his arrival. In order to sustain himself, Leeteg sold his boots and his camera, getting by on soup and bread.

In a never completed autobiography, he wrote of the jungles of Tahiti, saying that they “exceeded the glowing words of the travel folders.” In the same paragraph, however, he talked about the Tahitian people in not-so-flattering terms. He described lying in the road, doubled over in pain from ptomaine poisoning and being ignored by passersby.

“Tahiti seems to have a dearth of Good Samaritans,” he said. The only souvenir that he made note of was a sexually transmitted disease he picked up the night before he left.

“No, I can’t say that my first acquaintance with Tahiti made me vow to return some day,” he wrote, “Adding up and balancing the pleasure and the pain, I did not then care if I ever saw the place again.”

When he got back to his job, America was being strangled by the depression. There was very little work to go around, and the jobs that were available were being milked to provide employment for as many people as possible.

Leeteg caught grief from his fellow workers simply because he returned from vacation. They felt his return was essentially taking work away from them. They also resented him because he was unmarried and therefore didn’t need the work as much as a married man did. He was even put on trial by his union for working overtime to finish a job in a remote location, rather than returning the next day to complete it.

He had no interest in dragging his feet to stretch out work, and seeing his co-workers squabbling over work was beginning to make him bitter.

Then, a letter arrived from a friend he had made while in Tahiti. The letter said that a theater was going to be built in Tahiti and they wanted to hire him to paint the signs for the lobby.

Faced with continuing to struggle amongst featherbedders and a paltry paycheck in the U.S., Leeteg discussed his options with his mother, Bertha. Late in 1932, he stole some brushes from work and filled several empty mayonnaise jars with paint. With only his aged mother, a portable record player and his pilfered art supplies, he tossed his job to the wolves and left the U.S., bound for Tahiti, “where all the happy failures go.”

Leeteg had found a niche for himself by revitalizing and revolutionizing velvet painting, but there was still no market for his work, and certainly no critical acceptance of the medium. He occasionally sold a few paintings, but it was mainly to sailors for a few dollars. He would oftentimes trade a painting to a bartender for a bottle of whiskey.

A turning point in Leeteg’s career came when a jeweler named Wayne Decker visited Tahiti on a vacation cruise. He happened upon several of Leeteg’s velvets in a shop full of junk. He decided that he must have one of these paintings, but when he excitedly returned to the shop with his wife, all of the paintings were gone.

The shop owner didn’t know where Leeteg lived. So, Decker spent the rest of the day searching every bar in Tahiti, looking for Leeteg and leaving word that he wanted to buy some of his paintings.

Just two hours before Decker’s ship was to set sail, he saw a man fitting Leeteg’s description (a rotund, staggering American) approaching the ship.

Leeteg stepped up to Decker and said with a grin, “You must be Mr. Decker. Crawford told me when I found the loudest Hawaiian shirt I’d ever seen, it’d be you.”

Decker invited Leeteg down to his cabin. He stayed for a few hours and went on to tell Decker of his flight from the States and describing the method he had developed for painting on black velvet. Decker finally asked how much it would cost for Leeteg to reproduce some of the paintings he had seen in the junk shop.

“If you will give me that fancy Hawaiian shirt I will make one for you,” replied Leeteg. Decker took the shirt off his back and gave it to Leeteg, along with four more of his loudest aloha shirts and $200.

Tears welled up in Leeteg’s eyes. He said he was so moved because Decker was the first person who had trusted him since he arrived in the islands.

Touched by Leeteg’s generosity and thrilled with the quality of the paintings, Decker wrote to Leeteg, ordering at least ten paintings a year for an indefinite amount of time–for any price within reason. This standing order would stay in place for the rest of Leeteg’s life. Decker would eventually own over 200 Leeteg velvet paintings.

Decker was Leeteg’s first patron, and their arrangement allowed Leeteg to finally end his flirtations with abject poverty. Although this financial stability was beneficial to Leeteg for obvious reasons, it was equally important because it shored up his confidence. He was finally given an outside reassurance that he was on the right track.

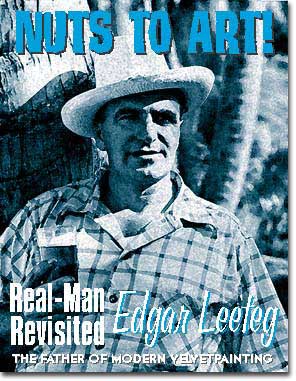

“Nuts to art. Genius is just the compelling desire to excel, to express one’s self, to give enjoyment to others, this plus nature’s gift of a super-abundance of energy over and above the requirements for daily living. A surplus of exuberance to share among those around us.

“…The so-called fine arts have been on the skids since the turn of the century, when impressionism was aborted into the birth of all “isms” of abstract painting. Art is, always has been and, if it is to survive, always must be emotional. To make it coldly intellectual by abstractionism and impressionism is to destroy it or mold it into a monstrosity that is better kept locked up in musty museums. I frankly would rather prefer to have my paintings displayed in a gin-mill rather than buried in a repository together with the rest of the dead art, which is where this modern crap will end up.

“I refuse to be converted. The other day one of these ‘artsy artists’ from the Metropolitan in New York was sitting right on this lanai and he did some sketching of this bay. He showed me his finished canvas. I wanted to vomit when he showed me what a sacrilegious abortion he painted of my beautiful Paradise. I was quite frank with him. I told him I had seen better similar art on a stableboy’s shovel!”

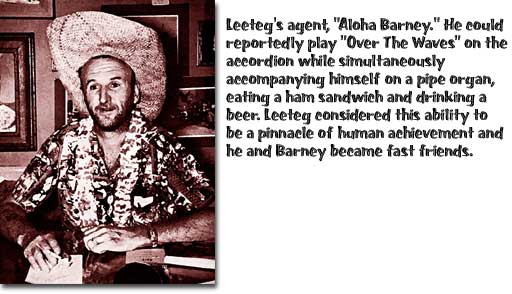

— a letter from Leeteg to Aloha Barney