Ab Jenkins: Son of the Salt

EXCERPT —

Utah’s 100 square-mile Bonneville salt flats are an expansive wasteland that claimed the sanity and lives of many settlers during the 1800s. Creeping across the sparse, blinding whiteness of the flats at three miles per hour was a brutal, three-day ordeal for these early settlers. It was common for them to be driven mad by thirst or mirages. Being bogged down in the mud of the outlying areas of the flats caused the infamous Donner party to enter the Sierras too close to winter. They were left to freeze and starve to death in the mountains, ultimately resorting to cannibalism to survive. But the territory that was the bane of settlers was a boon for speedsters of the early 20th century.

Because it was a hotbed of bicycle and motorcycle racing, Salt Lake City was known as “the birthplace of speed” at the turn of the century. It was here that a young Mormon carpenter named David Abbot Jenkins was introduced to motorcycle racing. Known as “Ab,” he competed in 1/2 mile races on dirt tracks as well as in cross-country motorcycle races.

A highway was put in through the salt flats in 1925. A friend who had worked on designing the road asked Jenkins if he would be willing to race an automobile down the new highway against the train as a part of the highway’s inaugural celebration. Jenkins accepted the challenge. Jenkins beat the train by five minutes.

Jenkins was convinced that the area had enormous potential for racing. He set about championing Bonneville as the next great land speed track. However, the more established tracks were the preferred venues for most racers.

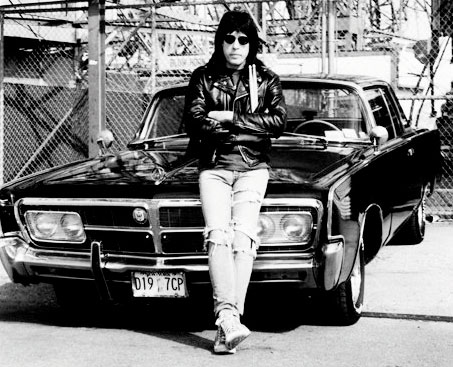

Jenkins was far from the stereotype of a reckless, speed-crazed thrill-seeker. He never considered himself to be a rough and tumble daredevil. In fact, he was very much a mannerly gentleman-sportsman who consciously avoided all things crude and vulgar.

Jenkins saw his races mainly as a test of his strength and fortitude, which he attributed to his dedication to restrained, modest Mormon living. “I owe the maintenance of my endurance ability to the observance of the Word of Wisdom of the Mormon Church,” said Jenkins, “which my good mother taught me as a boy. It proscribes the use of all forms of tobacco and liquor.”

His racing got the attention of the Pierce-Arrow automobile company, who invited him to come to their factory in Buffalo. Pierce-Arrow had developed a 12-cylinder engine, but couldn’t get it to out-perform their 8-cylinder. Jenkins was asked to see what he could do to improve its performance. After a few weeks of tinkering, he raised the output of the engine from 130 horsepower to 175 horsepower.

In 1932, Jenkins got the idea that running the powerful new 12-cylinder on the salt flats for a 24-hour endurance run would be perfect opportunity to show what both Bonneville and the engine were capable of. He told Pierce-Arrow officials that he would run the car 2,400 miles in the 24 hours. They laughed at him. Undaunted, he set off to test the 12-cylinder Pierce-Arrow in Utah with the car and six new tires as his only equipment.

The whole set-up very rough and simple, but it would do the trick. With the help of friends, a 10-mile circular course at Bonneville was marked off with stakes. The run was timed with stopwatches. There were no facilities or tents set up on the flats. A sheep wagon was towed onto the course to provide some shelter for the timers and crew. Pulling the fenders and windshield off the Pierce-Arrow, Jenkins simply smeared his face with grease to protect his skin from the sun, put on a pair of goggles, hopped into the car and raced onto the track.

As he raced, the timers signaled his speed to him with large signs. For amusement, Jenkins wrote notes back to his crew on a notepad anchored in the middle of his steering wheel and then threw the missives to them as he thundered by at over 100 mph.

He stopped to refuel every two hours, but he never left the driver’s seat of the car for 24 hours straight. When he finally got out of the car at the end of the run, he was stone deaf from the roar of the engine. Rather than running the 2,400 miles he had promised the Pierce-Arrow people, Jenkins had run 2,710! His average speed for the 24-hour period was 112.916 mph–very close to a new world’s record.

In 1933, Jenkins arranged for his second endurance run on the salt, the first one that would officially go on the record. With a somewhat expanded base camp, Jenkins set out on another endurance race with the same Pierce-Arrow. Shortly after the race started, a violent storm erupted with winds gusting up to 60 miles an hour. Tents were folded to prevent them from blowing away and officials ran to their cars for shelter, but Jenkins kept racing. The torrents of wind and rain did little to slow his speed.

After the last gas stop of the run, Jenkins took out a safety razor and shaved while circling the track at over 125 mph and with no windshield. When the race ended, he hopped out of the car, clean-shaven and presentable.

In the summer of that year, England’s best land speed racers, Cobb, Campbell and Sir George Eyston came to Bonneville. Their attendance turned the salt flats into the mecca for land speed that it remains to this day.

With the giants of speed competing, world speed records were set and broken several times over the passing days. When Cobb’s turn for an endurance run came up, Jenkins moved off the flats to allow him to race, but left all of his equipment for Cobb and his crew to use. At the one hour mark of his run, Cobb was on pace to clobber Jenkins’ record. His average for the first hour was 152.95 mph, compared to Jenkins’ 142.62 mph. He finished with a 24-hour average speed of 134.85 mph, beating Jenkins’ previous best of 127.229 mph.

Jenkins had helped another driver defeat his own record and was happy to do it. It was all in the spirit of friendly, sporting competition and helped to establish Bonneville. “Cobb is a great fellow,” said Jenkins, “and it was a pleasure to do everything in our power for him.”

In 1939, Jenkins brought a new car to the flats. It was the mammoth Mormon Meteor III. Built on a 142-inch wheelbase with specially-made 22-inch Firestone tires, it used the same Curtis 12-cylinder airplane engine from the Mormon Meteor II. The car was nearly 21 feet long and was once again engineered by Augie Dusenberg. It was designed to run with two airplane engines, although only one was ever installed. It generated 750 hp at 2,000 rpm and its top speed was 275 mph. It was estimated that it could run at 400 mph with front and rear supercharged engines installed. It had a 112 gallon gas tank and got three and a half miles to the gallon at 200 mph.

Shortly afterwards, a movement was begun to elect Jenkins as the mayor of Salt Lake City. Although he entered the mayoral race late, never spent a cent of his own money and never made a single speech, he won the election.

In 1940, the “Racing Mayor” made one of his most amazing runs at Bonneville. He had made many 24-hour runs solo, but Jenkins now opted to use a relief driver. (He was, after all, 57 years old!) His relief driver was Cliff Bergere, who had raced at Indy and was also a motion picture stunt driver.

On one lap of his run that year, Jenkins ran 189.086 mph. Over the 24-hour run, Jenkins drove 14 hours and Bergere drove for 10. When Bergere got out of the car after his shift, his hands were blistered from hanging on the steering wheel to keep the car on course. He told the Salt Lake Tribune, “I’ll take my hat off to Jenkins. Any man who can drive a car for six solid hours on this course at the speed that Ab got out of the machine is a marvel. I have never seen anything like it.”

The Mormon Meteor III broke 21 records that year. His average of 161.180 mph for a 24-hour run would not be broken for decades to come.

Jenkins was a breed of consummate sportsman-gentleman whose polite and honorable conduct today seems as rare and quaint as the open-cockpit Pierce-Arrow that he first raced at Bonneville.

He was extremely proud of having only been injured once during his many record runs. His endurance races at Bonneville put cars through exhaustive testing that helped to make production cars and tires safer for the everyday driver.

Over the period of his racing career, Ab Jenkins held and broke more records than any other person in the history of sports. His 24-hour record of a 161.180 mph average stood for 50 years, being beaten in 1990 and only by a team of eight drivers. Jenkins’ record for the 48-hour endurance run still stands to this day.

Excerpted from the print edition of Barracuda #11.